A Call For Youth Liberation, by Alexander Khost

“Why are those teachers screaming at those kids?” my son James asked me, with a look of true shock and concern on his face. He was observing some teachers across the cafeteria as they were berating a group of students sitting at lunchroom tables. It was James’ first time attending a public school class. The Agile Learning Center he attends was still closed for the holiday break, and he had decided to tag along for an after school class I teach in a public middle school in Brooklyn, New York. I faltered and replied something along the lines of, “Well, they’re trying to get those kids under control, I guess.”

At eleven years old, my son thankfully had no previous conception of why adults would scream at kids in a school setting. However, for me the scene was unfortunately commonplace, having been raised in a conventional school setting and now spending significant time working in such environments. James’ remark stayed with me: why is it that adults find it acceptable to scream at children or otherwise treat them as their subordinates? Why is it that adults look to control children? Is there a better way than fear-based authority to rear our children? And most importantly, if so, then what can those children do about the situation?

These are some of the observations and questions that will be addressed in this column, along with suggestions for resolutions. We will be taking a critical look at children’s environments and empowering young people by giving them a voice through their words and illustrations right here in this space. Welcome to Voice of the Children.

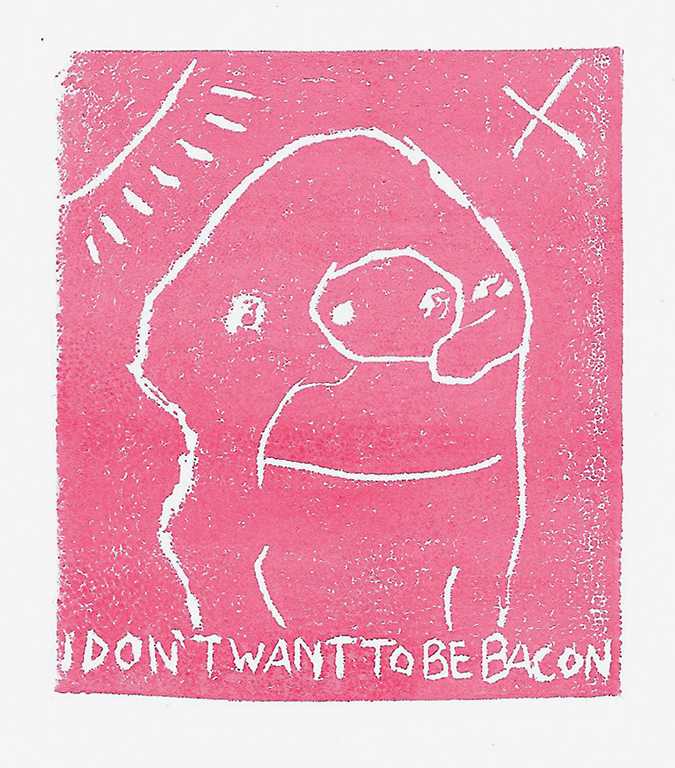

linoleum print, 2017

Children encompass the largest group of oppressed people around the world and throughout history, though they are not often recognized as such. The drive to emancipate children through Self-Directed Education and trustful parenting is, in fact, the most recent civil rights movement, and it should be acknowledged as such. I encourage skeptics of this statement to consider the viewpoint of any oppressor in a civil rights movement; they likely scoff at such statements and, with little thought, explain it away through convention, wrongly assuming that the way things have been done is simply the way they necessarily have to be.

For example, the widely accepted use of time-outs as a parental disciplining tool is actually an experience of “social isolation and rejection” that, for the child, is “experienced as shame.”1 Time-outs were invented by the behavioral psychologist B. F. Skinner as a way of manipulating children’s actions rather than helping them in “constructing an image of themselves as decent people.”2 In the end, there is a group of people being treated as less than human, being put down by another group of people in power who dictate conventionality. This is the description of oppression and it necessitates a call for liberation.

What is interestingly different about this particular civil rights movement is that all adults were once children, and so, nearly all individuals have been a victim of this form of oppression. This begs the question, if most everyone has experienced the abuse inherent to being an oppressed child, then why does the situation perpetuate itself from generation to generation?

Brazilian educator and philosopher Paulo Freire famously provides the answer that, “the oppressed, instead of striving for liberation, tend themselves to become oppressors” and that “only power that springs from the weakness of the oppressed will be sufficiently strong to free both [the oppressed and the oppressor].”3 If this is true, then ending the cycle requires that there be liberated children who grow into autonomous and responsible adults; the change must come from children themselves with the aid of adults who are willing to forge forward “with, not for, the oppressed… in the incessant struggle to regain their humanity.”3

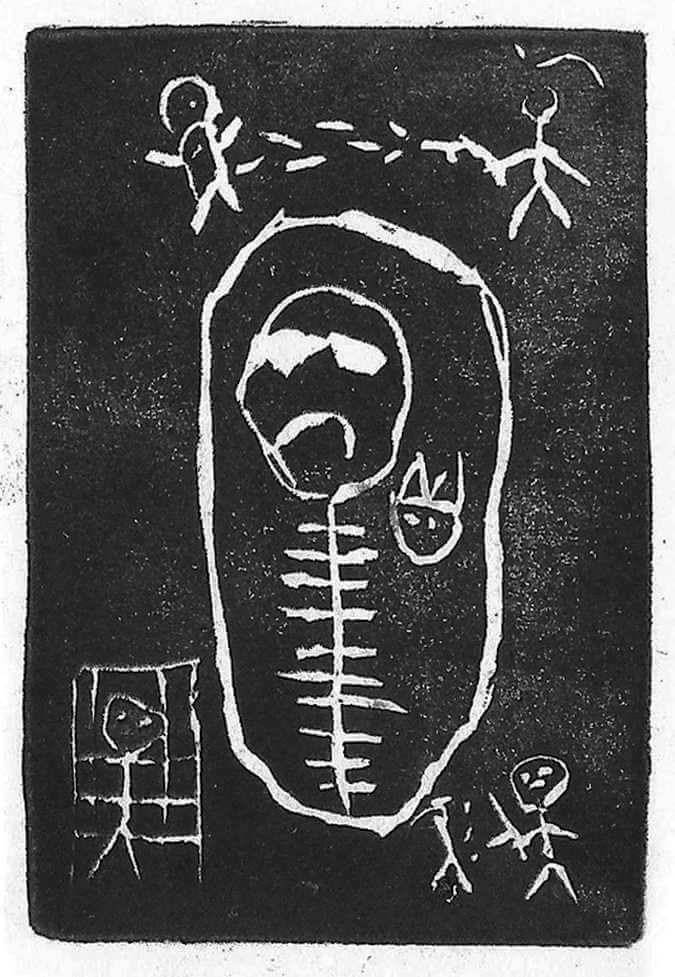

11 year-old girl who has spent her entire life in jail,

by Mateo (age 11), linoleum print, 2018.

These injustices against children are pervasive in our culture, making them that much more dangerous as they are accepted as the norm. For example, look at how ingrained it is in our society to assume and accept that all children dislike school. I have repeatedly heard adults say to my children, “Lucky you!” when the adult hears my children are off from school for one reason or another. At this my kids, who attend a Self-Directed Education learning center, used to look at me in confusion, and I would have to awkwardly explain to the adult, “Actually, my children like their school and want to be there.”

My children consequently now know this to be the sad universal understanding of conventional schooling. But let’s stop for a moment and think about how simply awful it is that every day, for the majority of their waking time, most children are knowingly and willingly placed in an environment that they have an aversion to. What message does this convey to children about our society, about their own interests, and about their ability to make future decisions?

We place lower and lower expectations on our children’s abilities and thus, they learn to treat themselves in such a manner. This psychological phenomenon is known as the Golem effect and has been widely studied and proven in educational settings.4 Incidentally, the opposite has also been proven to be true, treating someone with higher expectations typically increases their performance, a phenomenon known as the Pygmalion effect, made famous by Eliza Doolittle’s line in George Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion (better known through the musical adaption, My Fair Lady), “I shall always be a flower girl to Professor Higgins, because he always treats me as a flower girl, and always will; but I know I can be a lady to you, because you always treat me as a lady, and always will.”5 Put in other words: if we treat children as incapable and irresponsible, they will act as such; but if we treat children with respect, they will respond with dignity and accountability.

One large way in which conventional society controls children is in the name of “safety,” causing a widespread epidemic of incapable youth. A friend who ran an organization in New York for over thirty years that brings art classes into inner city schools told me that she studied the reports that quantified children’s basic skills. She was alarmed to discover that in the 1970s and 80s the average four year old could capably use scissors but by the start of the 21st century that number had climbed to the average seven year old.

In the writer and activist Matt Hern’s exceptional book, Watch Yourself: Why Safer Isn’t Always Better, he writes, “From car seats to bike helmets to street-proofing classes, kids have been recast as precious and fragile commodities in a world bent on trashing them. More importantly, they need to be protected from trashing themselves. The ideal safety is about predictability, a desire that runs in the face of traditional faith in the exuberance of kids and the centrality of self-reliance.”6

Starting in the home right after birth, conventional parenting tells us to: impose when children should eat and sleep rather than listen to their bodies; stop children from picking up and exploring dirt on the floor and replace it with expert certified hygienic non-choking toys; dictate how to “play nicely” through sharing prior to an age when children developmentally can perceive empathy; and determine when and how their time will be used. In fact, even before birth, mothers are told to not listen to their own bodies and that only experts in a hospital can successfully and safely deliver that “precious and fragile” child “commodity.”

When they reach school age, conventional education reinforces these values by telling children that they must: ask permission to use the bathroom; sit at a desk despite their energy and desire for socialization; be subdivided unnaturally to spend the majority of their (subdivided) time only with children born in the same fiscal calendar year; be handed a hierarchically predetermined rigid curricula and be over-tested by a system that does not at all take into consideration the individual needs or interests of that particular child.

Our political system makes sure that these children understand that they: are not full fledged citizens and cannot be trusted in their vote until they are eighteen; cannot be trusted to follow their own pursuits and so are placed in compulsory schooling along with labor laws that do not allow them to work even if they wish to do so; and do not have control over their own bodies, allowing parents to have legal control over where their image is shown, when they can walk out the door or even decide the length of their own hair.

These are but a few of the seemingly endless ways in which parents, institutions and laws strip young people of their rights on a daily basis, making such controlling actions and demeaning treatment of individuals now commonplace, mechanically followed, and unquestioningly accepted.

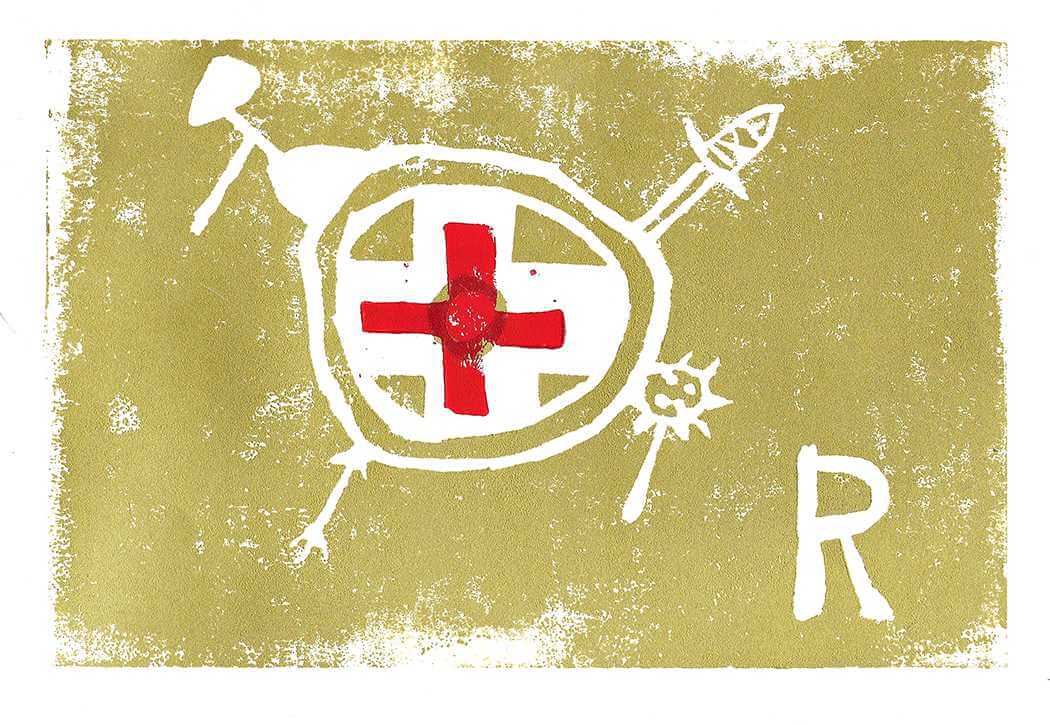

by Myra (age 10), colored pencil on paper, 2018

For this article and with their permission, I interviewed two children who have experienced both conventional schooling and Self-Directed Education, and I researched material from adult authors who are “on the side of the child”7 in order to generate some practical views on working with the oppressed in this civil rights movement.

Myra, a ten year old who attends a homeschooling coop but was originally schooled in a more conventional environment distinguished for me between “productive” and “unproductive” things one learns. Productive things, she told me, her parents encourage her to do, such as math, her fashion scrapbook, and the timeline of the American Revolution she is making. Unproductive things she listed off included playing Dungeons and Dragons with me at the homeschool coop, and reading. Or rather, these were the “fun things,” she explained. But then she thought for a moment and quickly added, “but productive things can be fun too.”

In my own reflection of Myra’s choice of words, I wondered if perhaps that which she has come to perceive as “unproductive” could also actually be, well, productive. In our Dungeons and Dragons group, for example, we read and write, use basic arithmetic, learn about history, cooperation in a group setting, and Myra’s favorite: storytelling. One of Myra’s adventuring colleagues, who was previously illiterate, finally decided he wanted to learn to read because he wanted to play Dungeons and Dragons more effectively. And so, he taught himself how to do so while sitting on wrestling mats sifting through pages of The Monster Manual for hours at a time.

When I asked Myra what advice she had for children who may not get as much freedom as she now has in choosing how to spend their time, she said, “Talk to your parents about how you feel. Try to set up your time in a way where you have a little bit of time for yourself every day.”

Daniel Schaffer, my friend and the father of a Self-Directed graduate of the Brooklyn Free School where we met years ago, once explained to me the idea of “Special Time,” a technique he learned at Re-Evaluation Counseling (RC). He had been using it with his daughter since she was a baby, a technique quite similar to Myra’s suggestion for setting up daily time for one’s self. But in this case, it is the adult spending time with the child where the child is in control of how their time is being spent together.

The parent and child (in this case, as Special Time in RC can be done with adults working with adults as well) set aside a fixed amount of time, say an hour, for effective listening, where the child leads and the parent follows without judgement or control. The trust and communication developed during these “little bits of time” can yield great benefits to the child’s confidence as well as the parent-child relationship, “The young people can feel that the parent is on their side and will begin to show the parent, often at times other than special time, the parts of their lives that they often keep to themselves.”8

But sometimes adults are afraid of giving up control or don’t see the value in handing over time and decision-making power to children. In this case, children may have to demand their rights, put on demonstrations, and even practice civil disobedience.

The Little Red School Book, a book originally published in Danish in 1969 that “encourages young people to question societal norms and instructs them on how to do this”9 includes a section entitled “Demand your rights, but be polite.” It tells children, “you shouldn’t put up with continued bad or unfair treatment… Remember that you have rights too.”10 One suggestion the book gives its young readers is how to prepare for a demonstration at school:

– Try to explain the problem to your parents, but don’t count on getting their support.

– You should be prepared for the worst.

– You should be prepared to get punished.

– You should be prepared for newspapers sometimes distorting the facts and being against you.

– You should be prepared for some of your friends to give in when parents or teachers threaten punishment10

While children are typically aware of unfair treatment and demonstrations are an excellent way to voice collective concerns and objections, often times in conventional schooling environments they feel powerless about the situation; the above list can seem overwhelming. And unfortunately for children, their HR department is typically staffed by the offenders.

“Kids should have rights. I’m a kid, and I don’t want to be controlled,” said my nine year old son, Oliver, recalling a brief period in which “I was at public school for five months, and I really hated it there. I was scared to speak up.” Now he is in a Self-Directed Education learning environment, and he feels that he has the support and confidence required to voice his needs and concerns, “Now I can speak up, and I’ve told that I hated it [in public school]. I think teachers there just think that we are dumb and we don’t know anything.”

When I asked Oliver about how to speak up he said, “Civil disobedience is good because it is not listening to the authorities but it is being polite about it. If someone is yelling at you or telling you to go to your room, using civil disobedience would be good. It would be just standing there and them most likely yelling at you. I would feel scared. And most likely you would for your first few times too. But then you would feel brave. Hopefully then people listen to you. If that doesn’t work, I don’t know what does work.”

Since children’s legal rights are typically held by their guardians, their own representation comes from an adult perspective. And if money is power, children are helpless since any money they may possess is also handled by adults. They cannot work to raise funds in their own defense or to break free from the controlling power (and when they can start working at fourteen, they are taxed without representation because they cannot yet vote. Perhaps it is time for teenagers to dump tea in a harbor?) The skeptic may say, “But children are young, they are inexperienced. Surely they cannot be making governing decisions and controlling money. Surely they need to be reigned in until we have taught them how to be responsible.” And so, paradoxically, society obstructs children’s abilities to make decisions for “their own good” and thereby denies them the thing they need most for growing up to be responsible and self-governing: practice.

It is time that the word “childish” be considered derogatory and that we expose the mistreatment of young people in society. In 2021 we think of such ideas as commonplace when it comes to Social Justice movements such as LGBTQIAPK, #MeToo, and Black Lives Matter. It is time that we now also look critically at our treatment of children and stand with them for their rights as human beings.

[1] Lamia Ph.D., Mary C. “Why Time-Outs Need a Time Out,” https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/intense-emotions-and-strong-feelings/201606/why-time-outs-need-time-out, 2016.

[2] Kohn, Alfie. “Why We Shouldn’t Focus on Students’ ‘Behaviors’,” http://www.alfiekohn.org/behaviors/, 2006.

[3] Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Continuum Press, 1970. 30th Anniversary Edition, 2002.

[4] Wikipedia. “Golem effect,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golem_effect.

[5] Shaw, George Bernard. Pygmalion, http://www.bartleby.com/138/5.html.

[6] Hern, Matt. Watch Yourself: Why Safer Isn’t Always Better, New Star Books LTD, 2007.

[7] Neill, Alexander Sutherland. Summerhill, A Radical Approach to Child Rearing, Hart Publishing 1960.

[8] Re-Evaluation Counseling. “Special Time,” https://www.rc.org/publication/present_time/pt110/pt110_49_c, 2016.

[9] Wikipedia. “The Little Red Schoolbook,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Little_Red_Schoolbook.

[10] Hansen, Søren and Jesper Jensen. The Little Red School Book, Stage 1 1971. Hans Reitzels Forlag, 1969.

Alexander Khost (he/him) is a father and youth rights advocate. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Tipping Points and founder of Voice of the Children. [This article was first published on Tipping Points in 2018.]