15 Ways to Reimagine Education

15. The Education System is Outdated. Create a New Model for the 21st Century.

School is a cultural norm in our society. Children have been schooled for as long as we can remember. It’s a tradition that most of us wouldn’t think of questioning, so it’s hard to imagine that there could be another way to approach education.

Most people would assume that if a child wasn’t at school five days a week then they weren’t being educated. However, it’s important to recognise that schooling isn’t the way education has always been done.

It is even more important to understand how schooling came about, because it would be all too easy to assume that the schools our children go to today are a result of tried and tested systems thought up by educational experts.

In fact, the schools that we see around us are not products of science and logic; they are products of history (Gray, 2013), and we must urgently question how relevant schools are for a 21st century workforce and lifestyle.

This short film by Next School illustrates how the traditional system of education was designed in the industrial age and is now outdated and ineffective:

A Short History of Education

Primary source: Free to Learn, by Peter Gray

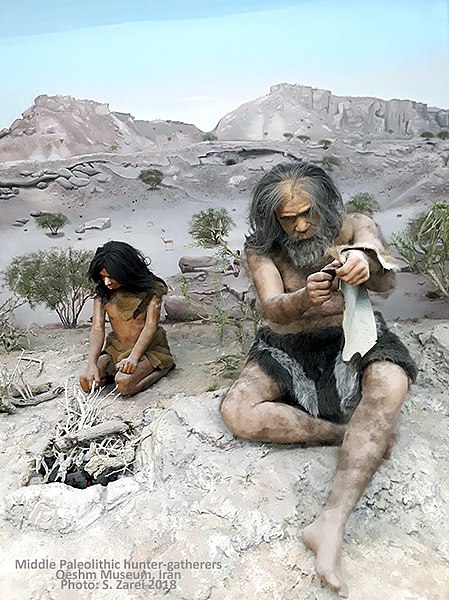

Stone Age Hunter-Gatherers: 2.5 million years ago, until approx 12,000 years ago

For hundreds of thousands of years humans lived as hunter-gatherers whose parenting and educational philosophy is described as trustful.

Education would have been through self-direction and children would have been allowed to spend most of their time playing and exploring freely.

They would have learnt naturally and contributed to the community when they had the skills and maturity to do so.

Credit: Sepehr Zarei CC BY-SA

The hunter-gatherer way of life was knowledge-intensive and skill-intensive, but not labour-intensive. They had to acquire deep knowledge of plants and animals and develop great skill in crafting and using tools. They had to be creative in finding food and defending against predators. The work of hunting and gathering was exciting and joyful.

Anthropologists report that hunter-gatherers did not distinguish work from play as we do. Children grew up playing at hunting and gathering and moved on gradually to the real thing. They had no concept of work as toil.

Hunter-gatherers didn’t have to work long hours so they had abundant free time to rest, make music, crafts, tell stories, play games etc.

Agriculture: 10,000 Years Ago

The introduction of farming – when people learned how to produce rather than acquire their food – is widely regarded as one of the biggest changes in human history, not least for childhood and education.

According to archaeologists, this change happened at different times in different places around the world. Crop cultivation first appeared in Asia 10,000-11,000 years ago and in Britain about 4,000 years later.

Agriculture provided a steadier food supply. It eliminated the need to keep moving in search of food and allowed people to settle down and build houses and communities. With a steady food supply, people were also able to have more children.

It also led to the decline of freedom, equality, sharing and play. Successful farming required long hours of relatively unskilled, repetitive labour – ploughing, planting, cultivating, tending to flocks etc. With larger families, children had to work in the fields and help care for younger siblings.

Feudalism: 9th to 10th Century AD

As agriculture spread across the useable land in Europe and Asia, land ownership went hand in hand with power and wealth. In the feudal system the King was at the top and the serfs were at the bottom. Children of serfs worked from dawn until dusk in the fields. Others worked as servants and the ‘lucky’ ones worked for years as apprentices to tradesmen and developed skills that gave them some degree of independence in adulthood.

In medieval times the life purpose of those in the lower classes was to serve and obey those above them. It was in this way that education became synonymous with obedience training.

Capitalism Emerges: Middle Ages to the 18th Century

While some made a living by owning land, others made farm equipment, household furnishings and clothing, and they processed grain and other agricultural products which were purchased by farmers.

To facilitate the exchange of goods and services, money economies, lending institutions and capitalism emerged. People with money formed businesses and hired those without it as employees.

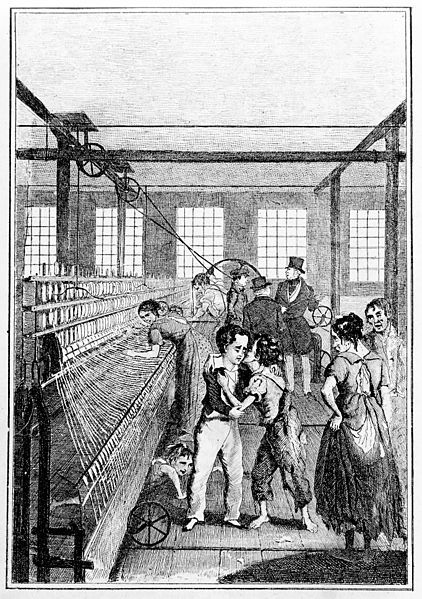

Factories, Child Labour and Church Schools

Source: Wellcome Collection Gallery M0013538EA

In England, factories capable of mass production began to multiply in the mid-1800s.

Child labour was moved from the fields into factories (or coal mines). Thousands died each year of disease, starvation, and exhaustion. A typical working day was from dawn until 8pm, six days a week.

Over this period, a network of church schools was established with the purpose of teaching children to read the Bible, to believe Scripture without questioning it, and to obey authority figures without questioning them. Those who worked in factories would attend Sunday School on the weekends.

In 1794 King Frederick William II of Prussia (a former kingdom of Germany) declared that children’s education would be a function of the state, not that of churches or parents. Other German states followed suit, along with other countries.

Compulsory State Schooling Introduced: 19th Century

England, which was the most fully industrialised country was one of the last to adopt Prussia’s system of universal, compulsory education. A major force against schooling was the high prevalence of child labour. Industrialists wanted to keep children in factories and parents needed the money they earnt. England also already had its network of church schools.

Credit: © Jorge Royan / http://www.royan.com.ar

The ruling classes had no interest in spreading literacy among the masses any further. If they could have stopped it, they would have. Finally, in 1870, the English Parliament passed the Education Act, which established mandatory schools for children aged 5-13 years.

Among those who pushed for the legislation were those who were genuinely concerned for children’s welfare in the factories.

Allied with such reformers, were members of the ruling classes who, like the German rulers, saw education as a means of controlling the masses. Schools were never established with the best interests of the child at heart, as people today might assume.

Schools were Set Up to Train Children for Factory Work and the Military

Mike Wood, Chair for the Centre for Personalised Education and advocate of home education, states how schools were set up to train children for an adult role in industry and the military. The Prussian model adopted by Britain – which currently prevails throughout the globe – was first devised following Prussia’s defeat at the hands of Napoleon. He explains:

“Prussia became one of Europe’s super powers, highly militaristic, ‘leasing out’ its soldiers as mercenaries. Despite a lack of other natural resources, it became an industrial powerhouse.

Did this benefit the Prussian people? Possibly, but it also sowed the seeds of the most highly authoritarian, militaristic state in Europe since Sparta. Sadly, it was inevitable that other aspiring nations would follow, if only to counter the threat.

The Prussian system of fore-shortened lessons and bells, strict militaristic hierarchy and discipline, and pseudo military uniforms, was intended to create a malleable working class with sufficient education to obey and follow the orders of their “superiors”, no matter how arbitrary.

So successful was this experiment that it was speedily adopted around the world by states adapting to the industrial revolution. So universal was its influence that few today can conceive of any other form of education. Education = school; School = education.”

In actual fact education and schooling are not the same thing. Education can include schooling but education is a much broader concept.

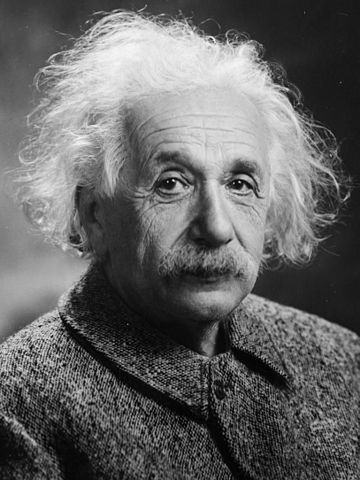

“Education is what remains after one has forgotten everything one learned at school.”

Albert Einstein

Photograph by Orren Jack Turner, Princeton, N.J. Modified with Photoshop by PM_Poon and later by Dantadd. / Public domain

Modern School Structure Remains Largely Unchanged

Once compulsory systems of state-run schools were established, they became increasingly standardised. Children were divided by age (and often gender) and passed along from form to form, like products on an assembly line. The length of the school day, school year, and number of years spent at school has grown steadily and the amount of homework and testing has also increased. School has gradually come to take over children’s and family’s lives.

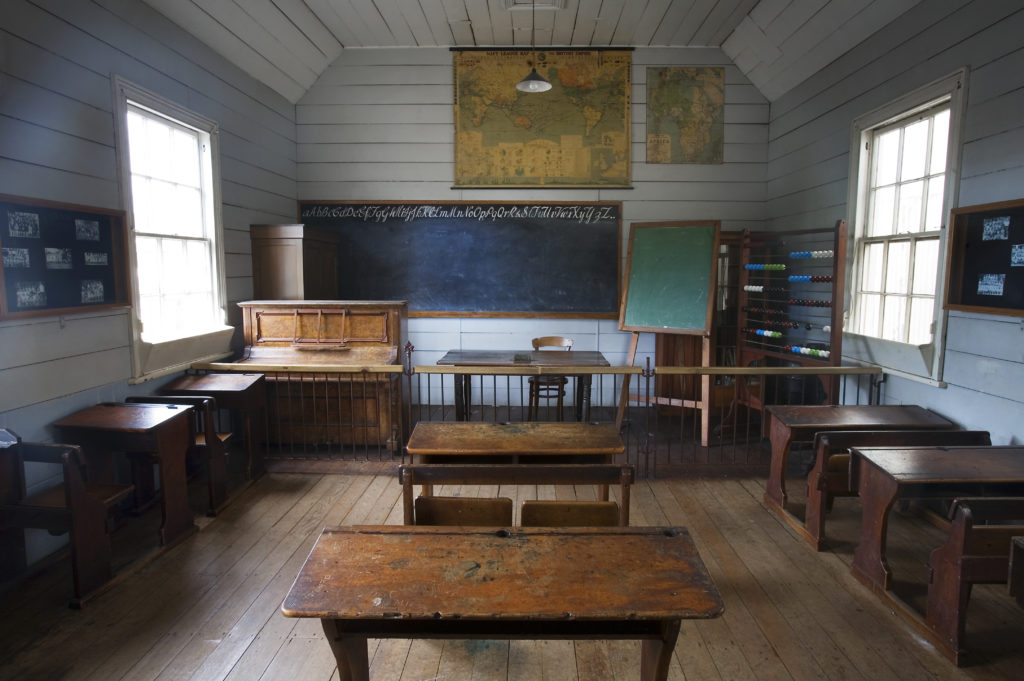

Apart from the increase in time spent at school, school structure and methods remain unchanged. A Victorian teacher faced with a class today wouldn’t feel too out of place.

Efforts to Change the System Just Offer More of the Same

In his book, Beyond Coercive Education, Peter Hartkamp says that many parents, children and teachers want the system to be improved, but the solutions proposed are in essence, more of the same: more teaching hours, more subjects, more tests, smaller classes, more homework, school at an earlier age etc. The current system may have brought positives in the past but at the moment it seems overstretched. We cannot solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.

After five generations of people who are ‘products’ of the education system, fundamental questions are no longer being asked:

Why do we have education? Why do we have year groups? Why do we constantly test children? Why is education coercive? Why do children need guidance? Why do we have diplomas or examination certificates?

Without asking these questions it is not possible to improve the education system.

Peter Hartkamp, 2016

Similarly, Dr Peter Gray says:

“Subsequent attempts at reform have failed because they haven’t altered the basic blueprint. The top-down, teach-and-test method, in which learning is motivated by a system of rewards and punishments rather than by curiosity or by any real desire to know, is well designed for indoctrination and obedience training but not much else.

It’s no wonder that many of the world’s greatest entrepreneurs and innovators either left school early (like Thomas Edison) or said they hated school and learned despite it, not because of it (like Albert Einstein).”

Innovation in Education has been Discouraged

Since mass education came about, education pioneers have tried to innovate, such as author Leo Tolstoy, Maria Montessori, Rudolf Steiner and democratic school, Summerhill founder Alexander Sutherland Neill. What their approaches all had in common was a trust of children to direct their own learning without coercion. But many of these innovations were contested by the establishment (Hartkamp, 2016).

Hartkamp explains that many governments regard any fundamental innovation in education as a potential risk to the education of children. While this may seem logical and reasonable, if you think about the context of the history of education (detailed above) it actually isn’t. Hartkamp quotes Professor Rob Martens (2014) of the Open University in the Netherlands:

“The biggest educational experiment of the last hundred years is the experiment that we now call mainstream education. After years of research I have not been able to find a scientific basis for mainstream education.”

Professor Rob Martens

Are Conventional Schools Relevant in the 21st Century?

As researchers and educationalists have pointed out, we automatically think of learning as work which children must be forced to do in institutions modelled on factories. We accept this as it is a cultural norm, but given the historical context of what schools were actually set up for, we must recognise that our tradition of schooling – which in the scheme of human evolution is really very new and unnatural – does not have the child’s best interests at heart.

We have gone from conditions in which learning for hundreds of thousands of years was self-directed and joyful, to conditions in which learning is making so many children feel helpless, anxious, and depressed (Gray, 2013).

Peter Hartkamp, along with many other advocates for progressive education argue that our system of coerced schooling is in fact a violation of children’s human rights and that the Department for Education has contravened the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). Hartkamp says:

“The educational model, as we know it today, was developed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries based on the needs of the society of that time. Children’s rights were agreed at the end of the twentieth century. However, there seems no explanation why governments failed to achieve children’s rights within schools over the past twenty-five years.

The Prussian education system focused on creating loyal and submissive citizens, bureaucrats and soldiers. In such an environment critical thinking is a moral sin, but critical thinking may be one of the most important, if not the most important skills for children to be successful in the 21st century.”

Peter Hartkamp

Education Policy Must be Turned on its Head

We no longer need to prepare children for work in factories. Business leaders, researchers and economists are telling us to prepare for a 4th industrial revolution. They are telling us that students are leaving school without the skills they need for adulthood and the workplace.

Children and young people require a different skill-set to those who were educated a century and a half ago. A growing movement of people believe it is time for change. Many say that a reform isn’t enough. As Reay (2012) stated, “Tinkering with an unjust educational system is not going to transform it into a just system.” (cited in Reclaiming Freedom in Education, by Max Hope).

Sir Anthony Seldon, former head teacher at leading independent school, Wellington College, made an impassioned critique of English education policy at the 2019 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) launch of the results of the Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa). He even performed a headstand on stage to demonstrate how education must be turned ‘on its head’! (See footage below.)

He said that the OECD must accelerate its focus on innovation in schools, and that schools should experiment more with a range of teaching methods. He added that society needed to listen to children themselves when designing policy, as well as entrepreneurs, athletes, trade unionists and creatives. He stated:

“Just about everybody gets it apart from Government education ministers around the world.”

Sir Anthony Seldon

Looking to the Future

According to Peter Hartkamp, the future already exists. The only problem is that it is not available to everyone. He refers to the democratic, self-directed approach to education which is practiced in Sudbury schools, as well as home education and the education system in Finland where there are no school inspections, no national tests and no school rankings. He says that these approaches are not only possible but they are successful.

Hartkamp’s passion for the Sudbury model of self-directed, democratic schooling is echoed by Dr Peter Gray in the film below from Chicago Ideas Week (2015). Gray reflects on his research which shows that the inherent playfulness, curiosity and willfulness of children has been honed by natural selection to permit each individual to educate themselves.

He questions why we are educating our younger generation in a way that so explicitly takes away these faculties and replaces them with standardised testing, and he reimagines an effective 21st century education: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G2BAJ_svbhA

Director of the film Schooling the World and Education Analyst, Carol Black also questions our current education system. In her talk, ‘Alternatives to Schooling’ she ponders what would happen if we removed the element of compulsion:

“What if we allowed our schools to operate the way human beings have structured their social learning relationships for 100,000 years, based in freedom, autonomy, consent and cooperation, instead of compulsion and control?”

In the film below (15 minutes) she paints a picture of what the alternative might look like.

Finally, you can read our article by Derry Hannam who outlines his vision for the future of education. A retired deputy head teacher and school inspector, Hannam is currently an international consultant in Education for Democracy and Human Rights. In agreement with the visionaries above he advocates for democracy and self-directed education. In his article he looks to the business world where companies are innovating by giving employees time to work on their own projects and he shows how schools could offer the same:

“Could it be that at last the natural learning potential of young people will come into alignment with the future requirement for collaborative and creative innovators? Could schools become places that nurture the social and economic entrepreneurs that the world needs?

Let’s hope so!”

Retired school inspector, Derry Hannam

Similarly, in the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Staff of 2030: Future-Ready Teaching report Esther Wojcicki advocates “20% time” to introduce self-directed learning into the schedule:

“This should be innovation time where students are given freedom to come up with their own idea of what they want to do, what they want to study, and how they want to do it. This can excite and empower teachers and reinvigorate their interest in the rest of their instruction.”

Esther Wojcicki, founder of the Palo Alto High School Media Arts Programme and an influential voice in education policy.

Get Involved

Please get involved by helping schools to enhance the student experience, and supporting campaigns which work to make positive changes to the education system.

Voices from the Sector

You can read stories from parents, teachers and other professionals to find out why progressive education is important to them and how education could be reimagined for the 21st century.

Further Resources

For a more detailed history of English education, please visit www.educationengland.org.uk which describes the development of our education system from AD43 to 2017.

Dr Chris Bagley from States of Mind gave a talk on ‘Shadow Cultures: How did we get here?’ in 2021 as part of the Education Futures in Action conference. He explored the historical forces and shadow cultures that have shaped the development of the English education system: Why do things feel stuck and what might the future hold?

Schooling the World – a must see film (1 hour) by Carol Black. ‘Generations from now, we’ll look back and say, “How could we have done this kind of thing to people?”’

Beyond Coercive Education, by Peter Hartkamp

Another Way is Possible – Becoming a Democratic Teacher in a State School, by Derry Hannam

Self Managed Learning and the New Educational Paradigm, by Ian Cunningham

Further Reading on Why Progressive Alternatives are Needed

Please visit 15 Ways to Reimagine Education